Along with jobs and commerce, the Bakken oil fields have brought organized drug crime and human trafficking to a state poorly equipped to handle either. New legislation went into effect August 1 that promises to start addressing the problem of human trafficking, particularly individuals or businesses who coerce minors into performing criminal acts, such as prostitution and drug dealing.

This amendment to the Uniform Act on Prevention of and Remedies for Human Trafficking clarifies the laws on trafficking, forced labor and sexual servitude—including patronizing a victim of sexual servitude—and makes these crimes a felony. The legislation defines aggravating circumstances as recruiting or enticing victims from shelters for victims, youth, runaways, or the homeless.

On the other hand, new protections are enacted for victims of human trafficking, including establishing victim confidentiality and limiting how evidence concerning the reputation or past sexual behavior of victims can be used by the prosecution. Minors who are coerced into criminal activity now have immunity from prosecution for delinquency for such crimes as prostitution, possession of drugs or drug paraphernalia, bouncing checks, petty theft and forgery. Any minor engaged in commercial sexual activity is considered a victim in need of child services. Individuals convicted of the above crimes while minors are encouraged to petition the court to vacate the conviction and get their record expunged. Victims of human trafficking can also bring civil action against traffickers and those who engage in commercial sexual activity. Finally, victims of human trafficking are automatically eligible for benefits or services from the state, regardless of immigration status, and even adds directives for helping undocumented victims qualify for a visa.

As part of the package, the legislature appropriated $1.25 million to help human trafficking victims, with a priority of establishing centers for victims to find services. The legislation also established a commission, which will be headed by State Attorney General Wayne Stenehjam.

What does this mean for residents of Indian Country, especially Fort Berthold, home to the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nations, where police report a fourfold increase in human trafficking, as well as associated crimes like drug dealing? The reservation has no shelters or other services for victims of human trafficking, although human trafficking groups have been working diligently to raise awareness of the issue among tribal members. The US Attorney's Office reported that fully half of the victims in sex trafficking cases prosecuted by the office were American Indian women and girls. The 20-officer strong Fort Berthold police force is struggling to respond to the surge in crime, with help from the FBI but without help from the state, despite the substantial oil impact money paid by the oil and gas development corporations.

None of the $1.25 million appropriated is earmarked specifically for services to tribes, and while the bulk of it is intended to be spent on services and programs in western North Dakota, there is no assurance that the centers will be convenient for Native victims of trafficking. Not all the 19 members newly appointed to the commission have been announced but so far, no representative from any of North Dakota's tribes has been named.

Wednesday, August 12, 2015

Monday, May 18, 2015

Law Enforcement Partnerships Prevent Overdose Deaths

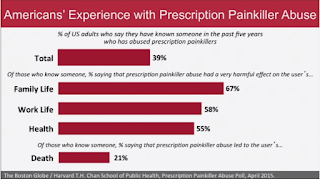

The statistics are grim. Prescription drug overdoses are up for the 11th straight year, and according to the CDC, 44 people die every day from a prescription drug overdose-- usually involving opioid painkillers, like Oxycodone. Increasingly, patients who become addicted to prescription painkillers turn to heroin as a cheaper equivalent. The surge in demand for heroin has led to a surge in the use of adulterants like fentanyl, which in turn is causing surging heroin-related deaths. The bright side is that people who do recover from opioid overdoses, and receive counseling and resources during their time of crisis, are more likely to make the effort to overcome their addiction. Law enforcement and first responders can be a key piece of that "intervention moment" when they are trained to administer Naloxone nasal spray (often known by its brand name of Narcan). Naloxone doesn’t substitute for emergency care but provides more time for medical units to arrive and treat the victim.

Washington's Lummi tribe was among the first in the nation to make Naloxone kits, along with prevention and education training, standard for law enforcement. The tribe acted in response to an"epidemic of drug overdose and death due to illegal drug use by community members of all backgrounds." In partnership with Lummi public health agencies, Lummi Nation police officers were trained to recognize the signs of opioid overdose and to respnd appropriately. Within six weeks of training, officers had prevented three deaths.

Recently, the Suquamish tribe announced a partnership to equip and train all officers, as well as members of the general public with Naloxone kits. When these tribal communities saw an increase in prescription drug abuse and then heroin use, the tribal governments, health departments, law enforcement and community members put their heads together as to how to respond. The tribal councils passed "Good Samaritan" laws to ensure that someone trying to help would not be liable for the outcome. Tribes worked with local pharmacies to keep supplies of the kits available, and to distribute kits and training to individuals.

Tribal first responders may need to work around state laws regarding the administration of Naloxone, especially where cross-jurisdictional agreements are in place. However, with federal encouragement, states are increasingly likely to encourage the widespread use of Naloxone in emergency situations.

Washington's Lummi tribe was among the first in the nation to make Naloxone kits, along with prevention and education training, standard for law enforcement. The tribe acted in response to an"epidemic of drug overdose and death due to illegal drug use by community members of all backgrounds." In partnership with Lummi public health agencies, Lummi Nation police officers were trained to recognize the signs of opioid overdose and to respnd appropriately. Within six weeks of training, officers had prevented three deaths.

Recently, the Suquamish tribe announced a partnership to equip and train all officers, as well as members of the general public with Naloxone kits. When these tribal communities saw an increase in prescription drug abuse and then heroin use, the tribal governments, health departments, law enforcement and community members put their heads together as to how to respond. The tribal councils passed "Good Samaritan" laws to ensure that someone trying to help would not be liable for the outcome. Tribes worked with local pharmacies to keep supplies of the kits available, and to distribute kits and training to individuals.

Tribal first responders may need to work around state laws regarding the administration of Naloxone, especially where cross-jurisdictional agreements are in place. However, with federal encouragement, states are increasingly likely to encourage the widespread use of Naloxone in emergency situations.

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

Surge in Fentanyl Laced Heroin Threatens Responders

|

| CNRB suits are recommended in crime scenes involving fentanyl exposure (US Navy photo) |

As prescription drugs have become harder to obtain and harder to get a high from, opioid addicts have been turning to heroin, both in Indian Country and throughout the nation. This demand has inspired Mexican cartels and other drug traffickers to start cutting the heroin they distribute with fentanyl. Fentanyl is a legal, but very dangerous drug that has legitimate use as a painkilling analgesic. It's 80-100 times more potent than morphine, and as little as 0.7 nanograms (one billionth of a gram) is enough to cause death in a user, especially combined with other drugs. The potency of the drug seems like a boon to manufacturers, but in reality, it's difficult to reduce pure fentanyl to levels safe for ingestion. The DEA, who recently issued an urgent warning about fentanyl and fentanyl analogues, estimated a single seizure of 5800 grams of fentanyl prevented some 46 million doses from hitting the street.

The upper threshold for lethal exposure is 2 milligrams, and can be absorbed by the skin, in the air, in food or in water. In general, only laboratory testing can establish the presence of fentanyl in heroin, making it even more dangerous for law enforcement responding to a crime scene.

The CDC recommends a minimum of coveralls, boots and gloves when responding to an area where the concentration of fentanyl is known to be below the level of acceptable exposure, which is listed as "undetermined." The CDC additionally recommends that responders wear full protective gear, including respirators and suits rated for chemical exposure, if the level of fentanyl contamination is unknown.

Tribal law enforcement faces a difficult balance of continuing to respond to emergency calls involving heroin use, distribution, and overdoses, and maintaining a safe distance until officer safety can be established. Police departments should stay on top of trends and note spiking trends in overdoses, which may indicate the presence of fentanyl in the supply chain. If the presence of fentanyl is suspected at a crime scene, serious precautions should be taken in investigating the area, collecting and transporting the evidence, decontaminating officers, victims and remains, and in testing the evidence.

The remedy for exposure to a toxic level of fentanyl is intravenous administration of naloxone. Just as some police departments are making naloxone kids part of standard issue equipment, the Blood Tribe of Canada is training tribal members to administer naloxone, as part of an effort to stem an epidemic of overdoses from fentanyl-laced drugs.

Thursday, March 26, 2015

George Sword: First Native Police Captain

|

| Captain George Sword, center Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

It may have been an issue of jurisdiction that inspired many akicitas to overcome their distrust of the government and sign up with the tribal police. Horse thieves from outside the tribe were preying on the Lakota horses, and without jurisdiction, there was nothing the akicitas could do. After hundreds of horses were lost in 1879, dozens of men signed up for the police. George Sword, also known as Man Who Carries the Sword, ably led the police for thirteen years, before retiring and becoming a tribal judge. Sword served his tribe as a medicine man, holy man, camp administrator and war leader. He felt his work as police captain continued this work, helping his people transition to the new era.

As head of the Pine Ridge Indian police, Captain Sword commanded 49 men, including many recruits from outside the tribe and maintained his traditional appearance and duties while serving.

Thursday, March 19, 2015

Native Values Matter with Community Policing

|

| Julia Wades in Water and Police Chief Wades in Water Montana State University Library, Special Collections |

Whether or not it's the buzzword of the day, many tribes traditionally practiced some form of community policing. A society or clan might have special enforcement or judicial privileges, but other members of a community would help set the norms, identify negative behavior, and help to find solutions when asked.

Julia Wades in Water, of the Blackfeet Nation, was hired as a policewoman in 1905 by her husband, Police Chief Wades in Water. The couple took their roles as elders and protectors of Blackfeet tradition very seriously. Wades in the Water was a member of the traditional Crazy Dog Society, which according to Blackfeet historian Curly Bear Wagner, were once the sole "police force" and remained a "very important organization."

As the first Native female police officer in the nation, Julia Wades in Water served her community for 25 years, managing the detention facility and assisting with female suspects. While her husband pioneered diversion tactics like making "troublemakers" provide restitution and do community service, Julia sustained many warm friendships among the Blackfeet and the non-Native people of northern Montana. This pioneering law enforcement couple were deeply invested in maintaining the values and safety of their community, and Blackfeet of that era remember them warmly for all their contributions.

We like to focus on the great partnerships that support community safety for a reason; successful partnerships (with top level buy in) represent the investment a community is making to turn things around for itself. Just like in the old days.

Tuesday, August 20, 2013

For Sam, From All His Relations

His “contemporary traditional Indian art” is iconic, showing people who grow like trees from their deep roots into the stars; people who are proud, strong, protective of their community of life and filled with humor and compassion. In a thousand ways, these people are just like Anishinabe artist and activist Sam English, who transformed from alcoholic despair into one of Native America's most highly regarded artists. Thirty years after embracing sobriety, the diabetes he has fought for a decade has taken its toll. Sam's energy to continue producing his extraordinary works of art is exhausted.

Sam’s gratitude for his recovery and recognition inspired him to give generously of his time and artwork to causes that support Indian Country’s recovery from historical trauma. In the PBS documentary Colores, he says, “My being an artist gives me the freedom to be involved with community. It gives me an opportunity to interact with my community. That gives me the energy to be creative about my community. It’s given me access to life, to be able to do this. To have people look at my art and like what I do, that grounds me. Reminds me of where I came from. Reminds me that I have a contribution to make to my community.” Indeed, there is hardly a single cause—from domestic violence and child protection, to alcoholism and diabetes—that Sam English has not given to and created art for.

Today Sam’s community, including Anglos, Hispaños and Indians, is just waking up to the fact that he has reached the time of his much-deserved retirement. In retirement, as during all the years of his working life, an artist's income is totally dependent on selling his art. Planning for the future, Sam has salted away paintings over the years in the hopes that they would provide a steady income in his golden years.

The collected paintings of Sam English constitute an unparalleled treasure trove of public art, created by the Native artist in cooperation with countless government agencies and non-proft organizations, as well as many original pieces. True to his legacy in community activism, each image makes a strong statement about Native American strengths and how we can help each other to build a better future.

Sam hopes that selling his life’s work will provide him with an adequate retirement income, but he is hoping to find a single buyer for the collection, like a large museum, a tribe, or a private collector.

As a man who never turned away from an open hand or a good cause, it's up to us—all his relations—to step in for him, by helping to find a buyer for his magnificent life's work. Some of us might know acquisitions directors who might take up the cause. Some of us might be able to write letters to the Heard, NMAI, tribal leaders or private collectors and let them know how important Sam's art is to you.

Sam said of his art, “I want Indian people to look at it and say, ‘Hey, this is a good rendition of who we are and invokes all the things that make me feel good about myself.’” Anyone enjoying Sam’s art, or his company, is inspired both to feel good and to do better for each other.

Recommending Sam's art to your friends with money: Free

Sam English coffee table book: $47.98

Sam English signed Tribute to Wilma Mankiller: $335.00

Original Sam English paintings: Price available on request

Helping Sam create the retirement he deserves: Priceless

Sam’s gratitude for his recovery and recognition inspired him to give generously of his time and artwork to causes that support Indian Country’s recovery from historical trauma. In the PBS documentary Colores, he says, “My being an artist gives me the freedom to be involved with community. It gives me an opportunity to interact with my community. That gives me the energy to be creative about my community. It’s given me access to life, to be able to do this. To have people look at my art and like what I do, that grounds me. Reminds me of where I came from. Reminds me that I have a contribution to make to my community.” Indeed, there is hardly a single cause—from domestic violence and child protection, to alcoholism and diabetes—that Sam English has not given to and created art for.

Today Sam’s community, including Anglos, Hispaños and Indians, is just waking up to the fact that he has reached the time of his much-deserved retirement. In retirement, as during all the years of his working life, an artist's income is totally dependent on selling his art. Planning for the future, Sam has salted away paintings over the years in the hopes that they would provide a steady income in his golden years.

The collected paintings of Sam English constitute an unparalleled treasure trove of public art, created by the Native artist in cooperation with countless government agencies and non-proft organizations, as well as many original pieces. True to his legacy in community activism, each image makes a strong statement about Native American strengths and how we can help each other to build a better future.

Sam hopes that selling his life’s work will provide him with an adequate retirement income, but he is hoping to find a single buyer for the collection, like a large museum, a tribe, or a private collector.

As a man who never turned away from an open hand or a good cause, it's up to us—all his relations—to step in for him, by helping to find a buyer for his magnificent life's work. Some of us might know acquisitions directors who might take up the cause. Some of us might be able to write letters to the Heard, NMAI, tribal leaders or private collectors and let them know how important Sam's art is to you.

Sam said of his art, “I want Indian people to look at it and say, ‘Hey, this is a good rendition of who we are and invokes all the things that make me feel good about myself.’” Anyone enjoying Sam’s art, or his company, is inspired both to feel good and to do better for each other.

Recommending Sam's art to your friends with money: Free

Sam English coffee table book: $47.98

Sam English signed Tribute to Wilma Mankiller: $335.00

Original Sam English paintings: Price available on request

Helping Sam create the retirement he deserves: Priceless

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Parents, Tribes Not Enthused About Legal Marijuana

Marijuana is legal for recreational use in two states and for medical use in 19 states plus Washington DC (as of this writing). Investors are excited about opportunities to create a "clean American brand" for legal marijuana, and to invest in marijuana-laced edibles, a fast-growing sector. But lots of people from tribal governments to parents, are worried about the effects of legal marijuana.

Tribes can pass laws to decriminalize marijuana, but so far most tribes firmly oppose marijuana use on tribal land, even though legalization has created something of a jurisdictional nightmare for tribal police. Tribal members can use legal or medical marijuana outside tribal borders but not on tribal lands. In the absence of specific laws prohibiting use, non-Indians can use medical marijuana on tribal lands without fear of reprisal, since the Justice Department is refraining from prosecuting medical users.

However, that hasn't stopped the Salt River Maricopa-Pima Indian Community from seizing vehicles driven by state-licensed medical marijuana patients. The tribe released a statement saying,"People who transport drugs in any jurisdiction face the possibility that they will be arrested, prosecuted, and that the vehicles they use to transport drugs may be seized." The Northern Cheyenne Tribe refused an exemption for a medical marijuana user awaiting trial. Some tribes are even going head to head with states over local prohibitions against marijuana dispensaries. Other tribes, like the Navajo Nation (which lies in two medical marijuana states), are still debating decriminalization. The tax advantage of selling legal marijuana would benefit Washington tribes in the same way that tobacco sales do, which might be more appealing if tribes weren't so thoroughly tired of cartels running grow operations on tribal lands.

Tribal officials aren't the only one who want to put the brakes on legalization. A survey of parents in Washington and Colorado show that although a majority of parents support legalization, they want to ensure that legal marijuana stays out of the hands of children, and is not advertised or used in places where children can see it. Poison control experts who sounded an alarm about the dangers of children ingesting medical marijuana have advocated in favor of childproof containers, and education programs that advise parents to treat medical marijuana the way they would any prescription drug-- secured and away from kids.

For more about issues with prescription drugs and drug endangered children in Indian Country, join us at our upcoming two-day training in Spokane, WA!

Tribes can pass laws to decriminalize marijuana, but so far most tribes firmly oppose marijuana use on tribal land, even though legalization has created something of a jurisdictional nightmare for tribal police. Tribal members can use legal or medical marijuana outside tribal borders but not on tribal lands. In the absence of specific laws prohibiting use, non-Indians can use medical marijuana on tribal lands without fear of reprisal, since the Justice Department is refraining from prosecuting medical users.

However, that hasn't stopped the Salt River Maricopa-Pima Indian Community from seizing vehicles driven by state-licensed medical marijuana patients. The tribe released a statement saying,"People who transport drugs in any jurisdiction face the possibility that they will be arrested, prosecuted, and that the vehicles they use to transport drugs may be seized." The Northern Cheyenne Tribe refused an exemption for a medical marijuana user awaiting trial. Some tribes are even going head to head with states over local prohibitions against marijuana dispensaries. Other tribes, like the Navajo Nation (which lies in two medical marijuana states), are still debating decriminalization. The tax advantage of selling legal marijuana would benefit Washington tribes in the same way that tobacco sales do, which might be more appealing if tribes weren't so thoroughly tired of cartels running grow operations on tribal lands.

Tribal officials aren't the only one who want to put the brakes on legalization. A survey of parents in Washington and Colorado show that although a majority of parents support legalization, they want to ensure that legal marijuana stays out of the hands of children, and is not advertised or used in places where children can see it. Poison control experts who sounded an alarm about the dangers of children ingesting medical marijuana have advocated in favor of childproof containers, and education programs that advise parents to treat medical marijuana the way they would any prescription drug-- secured and away from kids.

For more about issues with prescription drugs and drug endangered children in Indian Country, join us at our upcoming two-day training in Spokane, WA!

Friday, July 19, 2013

Public Safety Hit Hard by Federal Cutbacks

The impact of sequestration is hitting public safety in Indian Country hard. Tribes have been cutting law enforcement positions and closing mental health programs. The horror stories are rolling in: The Oglala Sioux are down to one officer on duty at any time. The Navajo can't staff a jail that they built. The Red Lake Band of Chippewa are losing 22 BIA employees, mostly law enforcement officers. At Pine Ridge, where someone tries to commit suicide nearly every day, they have had to cut two counselor positions. Cuts to IHS programs have gone far deeper than expected, shuttering clinics and limiting emergency services.

While hundreds of millions have been cut from IHS and SAMHSA (mental health) programs, cuts to smaller programs are also having an impact. Programs designed to turn life around for kids have been decimated, from Headstart to the Tribal Youth Program, which had been helping kids discover alternatives to drugs and gangs. Tribal police are having more and more trouble staying ahead of the curve. As one officer explained, "It's really hard to be proactive when you don’t have enough staff."

What can be done? The National Congress of American Indians has already passed a resolution stating that sequestering funds for tribal activities amounts to a treaty violation, which still doesn't get boots on the ground or doctors in the clinic. Some tribes are cushioning the impact with funds from gaming, grant funds that have already been awarded or settlements. Some tribes are seeking partners in or out of the tribal community to help make up the gap. Join the discussion at our SafeRez group on LinkedIn to share ideas on how we can pull through this difficult time.

Labels:

Chippewa,

IHS,

mental health,

Navajo Nation,

NCAI,

Oglala Sioux,

Pine Ridge,

public safety,

Tribal Youth Program

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)